21st Century Collaboration

The field of composition has emphasized the social nature of writing for decades, but modern technology seems only recently to have embraced the term “collaborative” as a way to describe their interactive capabilities.

Indeed, Kenneth A. Bruffee’s ur-text, “Collaborative Learning and the ‘Conversation of Mankind’,” is as relevant to our understanding of new media today as it was to collaboration over twenty years ago. Bruffee’s (1984) historical view of collaboration highlighted the “social context” of “peer influence that had been—and largely still is ignored and hence wasted by traditional forms of education” (p. 638).

In this case, the process nature of collaboration relied on peers “learning to converse better and learning to establish and maintain the sorts of social context, the sorts of community life, that foster the sorts of conversation members of the community value” (p. 640). In other words, the process of community building—the most essential aspect of successful collaboration—was studied through conversation. Without relevant conversing, the community loses value and collaboration becomes increasingly more difficult to foster.

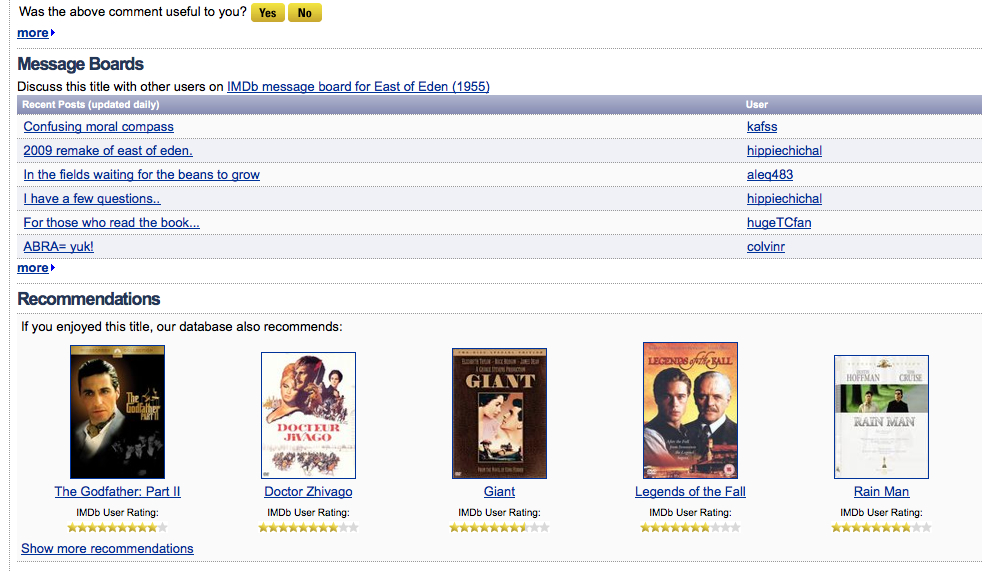

This is why Internet Movie Database’s (IMDb) recommendations and review sections have been so important to their success: the community is seen as relevant, and since the conversation has been archived so that a user will not feel like he has missed anything, every user is a potentially powerful member of the community bound by common interests (who likes what music, buys similar books, etc.) and common desires of self-expression. In essence, by all arriving at the site independently, but then contributing in individual ways, the successful Web 2.0 site IMDb has created Bruffee’s important “community of knowledgeable peers” (p. 644).

As a result, “a sense of community” often is referenced in a lot of literature about collaborative learning. However, we can infer that as it relates to technology, this sense transcends mere feelings of belonging and instead refers to a deeper sense of purpose. Nowhere is a sense of purpose more concrete than when a community is trying to produce something. And in the case of textual production online, that something is typically knowledge.

While it may be true to assume that most wiki projects aim for truth, accuracy, or coherence in their final products, the same cannot necessarily be said of other Web 2.0 sites. For example, are users on Amazon merely contributing text to help the site sell products? Are users on Twitter actively updating their statuses to build a linear timeline? And to the point of this article, are users on social network sites like Facebook actively attempting to co-author texts to produce knowledge relevant to others, or is this type of activity mainly a solipsistic form of sharing where users are interacting, but not collaborating? |

These questions will occupy scholars in composition and technology alike in the coming years. For now, though, it may be the most we can do to agree that Web 2.0 sites provide the clearest form of widely-available potential for collaboration than any technology preceding it. By providing users with ready-made communities who interact primarily via textual production, these sites offer undeniable overlap between social and academic fields of thought.

Of course, as discussed previously, considerations of authorship and power are complicated not only by social and academic forces, but also the commercial nature of most Web 2.0 sites. Ede and Lunsford (1990) point to “changes in copyright laws, in corporate authorship, [and] in computer-generated discourse [as] related to theoretical challenges to the ‘author’ construct” (p. 139). Because of the blurry lines drawn between ownership of collaboratively produced text, issues of ownership on websites can further the discussion of intellectual ownership in classrooms.

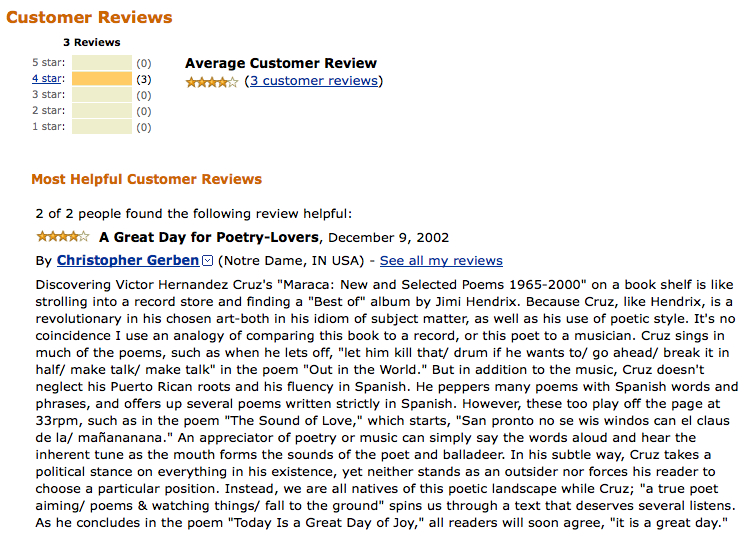

| For example, the case appears clear that a review of a book on Amazon is mine once it is posted and attributed to my name. However, is that review ultimately responsible for why a person purchases the item under consideration? If my reviews are helpful, and my textual contributions proliferate on the site, |

As a result, should Amazon pay me a commission? The text is mine, but the computer servers are owned by the site, and the “results” of the text are undetermined, with only the influenced user and the owners of the website benefiting.

This kind of hypothetical situation may provide an excellent discussion point for debating the merits of attribution and rewards within the academic system. Everything from good grades to tenure involving collaborative writing may be affected by the judgments such discussions produce.

Besides a sense of belonging for users, or economic gains by companies, textual production on these websites most importantly produces conversation; a sustained discourse. Nowhere is this more apparent than on Facebook’s Wall, where the situated space creates a meta-community of peers related to the owner of the profile.

Presumably, all of the participants on the Wall wish to form a community of peers who have the profile owner in common. A private email would just as easily form a person-to-person link, but a Wall posting builds upon a sustained dialogue even when the entries cover different topics. Taken together, these texts tell a story to any visitor of my profile that I am a particular type of person with particular kinds of relationships. But what happens when a friend offers something I do not like, or something that I do not desire to be known publicly?

This also becomes a power situation, but more so, the discourse of this meta-community takes on what John Trimbur (1989) attributes as an “abnormal discourse [which] represents the result at any given time of the set of power relations that organizes normal discourse: the acts of permission and prohibition…”(p. 608). Referring to Richard Rorty, Trimbur critiques his view of abnormal discourse as too heavily empowering the individual who is “ignorant of [the] conventions” of a given community (Rorty qtd. in Trimbur, p. 607). This abnormal discourse serves as a check on the normal (and normalized) discourse within a cohesive community.

On a profile Wall, this intertextuality of normal and abnormal discourses produces a complete text in much the same way classroom conversations and coauthored texts provide a view of the complements and conflicts of social interaction. What Web 2.0 offers those in the composition field though, is the continuously changing view of what it means to consent and belong to such a fluid community.

Though often asynchronous, texts produced collaboratively on websites should be viewed as elongated conversations whereupon users talk to each other to achieve common goals—advice on what to buy, gossip on shared acquaintances, or simply acknowledge someone else’s existence textually.

All of these textual interactions are borne from individual desires, but taken collectively produce a cohesive whole which demonstrates O’Reilly’s core competencies of harnessing collective intelligence and “trusting users as co-developers.” To see users as developers brings the conversation of collaborative textual production back to students in the classroom, and considerations of what pedagogical choices need to be reconsidered in light of this new technology.

On Walls, comment sections, and wikis, individual entries are both individual finished texts, and evidence of an evolving text. This public display provides what James A. Reither and Douglas Vipond (1989) look for in “writing as a collaborative process [which] gives us more precise ways to consider what writers do when they write, not just with their texts, but also with their language, their personae, their readers” (p. 856).

Composition instructors can instruct students how to write and then evaluate their final products, but collaboration privileges the invention and composing stages (pre-writing and writing) in ways that ideally challenge the writers’ ongoing thoughts about the composition process.

Web 2.0 sites provide instructors with a way of not only encouraging and facilitating these stages of the writing process, but also as textual evidence of the process. Technology now allows instructors to see the textual movements of authors as they interact with each other by not only comparing drafts and final products, but by allowing access to the milestone conversations and considerations that produce the text. In other words, the conversations of process become the text of the final product.

Sites like Facebook offer compositionists a new view of this power struggle in and out of academia specifically because their success is contingent on the collaborative nature present in writing groups and collaborative writing projects, and because the sites were borne outside of academia walls. On the current of ubiquitous WiFi access, this spatial divide allows those in the composition field to transgress traditional barriers of power relationships by walking the bridge between online and real spaces via these new sites.