Framing Questions and Definitions

In order to explore what Web 2.0 means to a lot of people in academia, business, and on the web, it may be helpful to first acknowledge the behemoth present on nearly every college and high school campus: Facebook.

Though initially started as a social site for active college students, it has welcomed in the entire world; by summer 2008, Facebook reported over 90 millions users (Statistics, 2008), with conservative estimates of the current college student population upwards of 20 million strong.

The site is the epitome of a popular and hyper-socialized Web 2.0 site. Both students and the general public are interacting textually on its platform from both academic and decidedly non-academic spaces. While increasingly ubiquitous WiFi and Internet access has made web-based interactions more popular, what separates this new generation of Internet sites from previous ones is its inherent social nature.

Some of the most popular sites on the web today—such as Wikipedia, which was visited by 107 million people in October 2007, making it the eighth most-visited site on the Internet (Rhys Blakely, 2007)—not only provide products for users, but rely on those users to enter text and interact with others in order for the site’s product to be desirable.

In essence, Web 2.0 sites allow users to collaborate with others to produce personalized experiences.

While no one site can encapsulate the diverse experiences a user may have on popular Web 2.0 sites, for this article I have chosen Facebook because of its dependence on user interaction via textual production.

Facebook is perhaps one of the most popular and representative examples of Web 2.0 technology: Internet sites that not only allow users to view information, but that function as “platforms” to interact with and revisit in the same way computer users run programs and store data on their personal computer desktops (Tim O’Reilly, 2005).

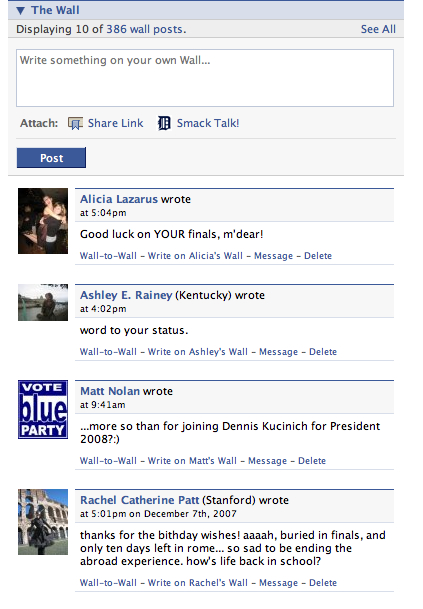

As a subset of the umbrella of Web 2.0 sites known as social network sites, Facebook is a clear favorite on campuses. Facebook’s rival sites like MySpace and LinkedIn respectively reach for the same users with similar motivations, but Facebook represents itself as a leader in this new version of Internet website by prominently relying on its “Wall” feature: an infinitely regenerating space where anyone can write on another person’s profile page.

While this is happening, the owner of the profile still

controls the space and the text: he can delete someone’s Wall posting

or he can add new friends or write on others’ Walls which may prompt

them to write back. As a result, each time someone adds text to his

wall, the entire profile changes. Thus my carefully considered page

from earlier is opened up to a situated conversation (including the one

shown here), which may affect how others view my identity through the

page. |  |

As the owner of my profile, I maintain a fixed yet evolving identity as

I invite others to coauthor the text of my profile page. As a result, a

profile page on Facebook becomes a site of social and textual

collaboration with complementary goals of self-expression and reaching

out to a real and relevant audience: both things compositionists strive

for in classrooms and collaborative assignments. Furthermore,

student-users are not simply co-authoring a text, by writing on each

others' profiles they are co-authoring each other.

Facebook’s Wall function is a further embodiment of new waves of

technology in that it provides compositionists lessons on three

distinct intersections of collaborative textual production online and

in the classroom.

My purpose in this article is to highlight three questions that Web 2.0

is addressing in a virtual space, which may have implications for

instructors of composition interested in collaborative theory and

practice in their own academic spaces:

• HOW is a text collaboratively authored? Web 2.0 sites rely on the production of never-completed texts to build expanding communities. This infinite production of text highlights the process nature of composing valued in composition and collaboration.

• WHERE is a text produced? Web 2.0 is online and virtual; it can be accessed and interacted with in classrooms and faraway countries. This function extends the classroom into realms of the physical and virtual extracurricular space.

By exploring these three parallel questions, we can further see the

relationship between Web 2.0 technology and collaborative textual

production in and out of our classrooms. Whether this technology is

used in the classroom, or simply acknowledged more fully as existing

beyond classroom walls, compositionists need to recognize how this

technology is affecting the nature of social and textual production in

the 21st century.

As we move deeper into this exploration, I consider these definitions essential to understanding the concepts of this article:

• Collaboration: Defining

online collaboration means ultimately determining whether or not users

are aware and/or complicit in their actions to produce shared

document(s). This article does not attempt to make this determination,

but instead aims to demonstrate the potential for explicit

collaboration that may or may not develop. Likewise, while Lisa Ede and

Andrea Lunsford (1990) quote Deborah Bosley as defining collaborative

writing “as two or more people working together to produce one written

document in a situation in which a group takes responsibility for

having produced the document” (p. 15), I herein agree with Nels

Highberg, Beverly Moss and Melissa Nicolas (2004) who believe that Ede

and Lunsford’s “concepts also apply to writing groups where individual

writers produce individual texts” (p. 4). This important conflation of

co-authoring and group writing will allow us to complicate definitions

of collaboration and collaborative writing by including work of

scholars like Anne Ruggles Gere (1987) who demonstrate writers/users

seeking both individual and group success.

• Web 2.0: For this article,

this highly debated term simply refers to interactive websites that

portray the “web as platform” (O’Reilly, 2004). These sites include

useful and successful websites that span social network sites

(Facebook), wikis (Wikipedia), suites of sites (Google), commercial

sites (Amazon), and other websites like blogs and file-sharing sites

that rely on user-input interaction to sustain content and community.

My use of the term Web 2.0 likewise considers Henry Jenkins’s (2006)

use of “participatory culture,” where “consumption becomes production;

reading becomes writing” (p. 60). By definition, there is no one,

single website or technology that is wholly representative of the Web

2.0 movement. Throughout this article I have primarily used Facebook as

a case study for Web 2.0 and social network sites mainly because of its

ubiquity and popularity with students. Facebook is likewise an

interesting site to study because unlike wikis, whose purpose is

largely to produce a type of knowledge that is “truth”; or blogs, which

primarily host one main author and myriad respondents, social network

sites like Facebook offer no singular purpose for users nor a clear

distinction between author and editor or producer and consumer, making

them a model of Web 2.0 as platform, and spectator culture as

participatory culture. Granted, user- and textual-interactive websites

are only one small part of the larger Web 2.0 picture (as there are

useful individual and non-textual sites available), but for the

purposes of studying student-user collaboration and composition, I have

focused this article on social networks for hopefully apparent reasons.

• Community: Composition

scholars have long debated the term “community” as a concept both

“appealing and limiting” (Joseph Harris, 1989, p. 21). Other fields,

however, tend to address the term through the lens of an eventual

purpose. While business scholars Etienne Wenger, Richard McDermott, and

William Snyder (2002) define communities of practice as “groups of

people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a

topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by

interacting on an ongoing basis,” (p. 4) and social-scientist Howard

Rheingold (1993) defines virtual communities as “social aggregations

that emerge from the Net when enough people carry on those public

discussions long enough, with sufficient human feeling, to form webs of

personal relationships in cyberspace,” (p. 5) this article looks to

simplify the working definition of community. By applying Kenneth A.

Bruffee’s (1984) broad “community of knowledgeable peers,” we can

assume that an online community is a group of users who both have a

common reason for occupying the same site and/or textual space, and who

likewise possess at least a basic understanding and mutual respect for

the practices, norms, and purposes that they share.

• Text: Any alpha-numeric

input (whether individual or part of a whole) by writers/users online

is considered text for this article. This includes (but is not limited

to) Wall posts, photo tags, comment boxes, etc. Gloria Jacobs’s (2004)

simple use of the word “text” to describe not only the alpha-numeric

input by a user, but all of the contextual implicit and explicit

interactions that inform that input succinctly considers online and

off-line input. Her study of instant messaging makes clear that no

single line of text in this medium can be taken out of the context in

which it is written and received. Likewise, a single post on a Facebook

Wall is a piece of text in the same way that the Wall taken at large is

considered text. This division is beyond the scope of this article, but

will undoubtedly be an important distinction for future scholars to

explore.