Making Friends Through Visual Interaction and Versioning

This fresh look at community exists not merely in conceptual ways, as it has in the past; theoretically there are communities of scholars on library shelves and in the ghosts of academia, waiting to be communed. But this change in view is the most important lesson Web 2.0 can provide those in the composition field regarding audience.

Communities like the one present on Facebook are mainly visual. Text on the Wall is made more powerful by the corresponding author’s profile picture next to it. Researchers have not yet begun to fully consider how this affects the way student writers perceive and enter into a conversation and community.

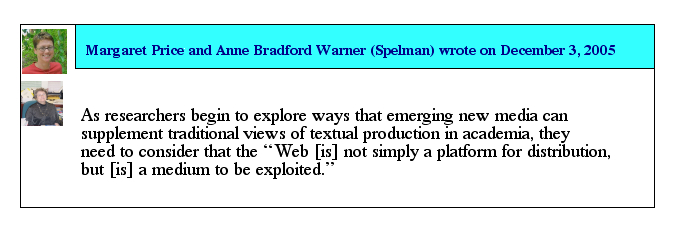

For example, note the difference between reading:

and seeing the same text with corresponding pictures of the authors (provided through their personal and program websites at Spelman College):

For example, take the simple scenario of an amateur author/researcher (played by me) contemplating a professional author/researcher’s (in this example, Andrea Lunsford) work. In the past, the amateur could cite cross-references, read supplementary material, or insert his own conjecture to address the professional’s points. However, with near-instantaneous friending and access via Web 2.0 sites, the amateur can ask the professional directly, such as in the following video:

Through email, personal homepages, and social network sites student-users are coming to expect to be able to connect with authors, researchers, and professors the world over. This expectation may not be fully realized as of yet in the classroom, and is undoubtedly something that should be rectified in future discussions of what it means to collaborate or research with established authors. Far from the calls of the death of authors, Web 2.0 has made them more accessible than ever.

Perhaps the most unchallenged misperception of the Internet is that it is merely a static space, a virtual world where people go to visit or interact before reentering into the “real world.” What compositionists and others need to recognize is that this perception only recognizes the finished (product) side of this reality. The truth is, newer Web 2.0 sites are making it easier to acknowledge the unfinished (process) side of each visit to this virtual space.

As users explore new areas of the web, they are not only experiencing and consuming data, they are creating data and, as a result, knowledge. This knowledge then becomes new aspects of the virtual landscape to be traversed by new users. This Web 2.0 that has “embraced the power of the web to harness collective intelligence” (O’Reilly).

What others know becomes what I know the more we interact online.

Successful sites present, collect, and re-present data so that users encounter unique interactions with others, and the virtual space itself, each time they visit. Citing one example, “eBay grows organically in response to user activity” (O’Reilly). As users sell more products and review each other’s actions, the site builds its own ethos. People trust the site and feel more at ease interacting on it.

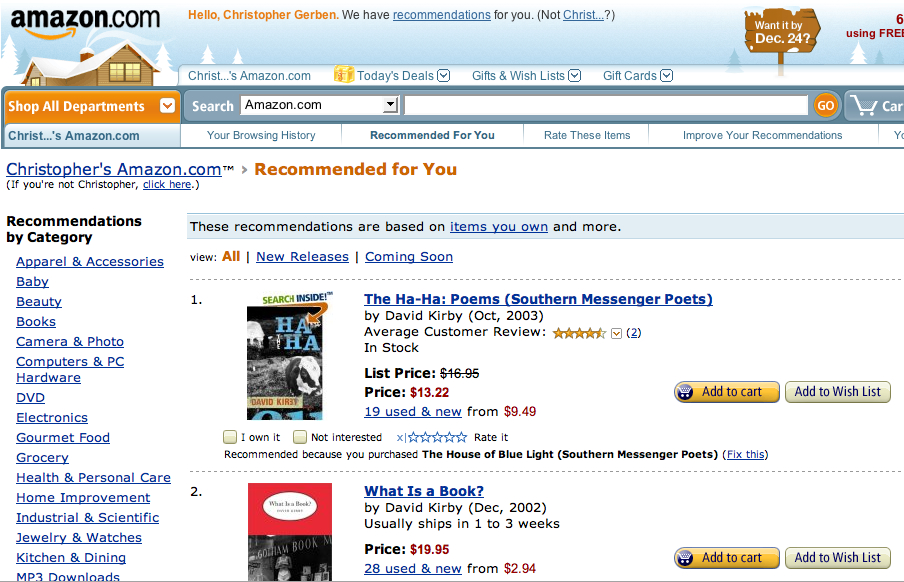

Likewise, Amazon sells more books than their competitors because of their focus on user |  |

Further, if I were to click on an item I would be

presented with not only a description of the product, but also user

reviews, another set of recommendations of books like this one, and a

catalog of the most popular products presumably related to the one I

am interested in. All of this enriches my online experience by making me feel part of a community, which implicitly encourages me to buy more, but to also contribute to the community by offering my own recommendations or knowledge-building. In short, a successful site like this asks me to collaborate to create a better product. And, as a happy customer, I willingly do.

Yet what can this commercial interaction teach researchers like Price and Warner who once concluded, “it is the urge to define ‘collaboration’ as a single thing, or to assume that the outcome of collaboration is a finished composition, that has led to problems with collaborative pedagogies of the past”? Sites like Amazon present two clear lessons on how Web 2.0 can teach compositionists new ways of thinking about collaboration.

The first is that by displaying and archiving all of my purchases and review history every time I log in, the process of my textual interaction with the site is always on display. My visits to the site are an infinite work-in-progress. This vivid display of process leads directly to the second lesson of community building through collaboration.

The rhetoric of the site—“recommended for you” and “products you’d also like”—suggests not only interactions with others, but a sense that those others, be they marketing programs (like Google’s AdSense which caters banner advertisements to my web activity) or actual users (who can track my activity by following my hyperlinked name), understand me and who I am. This is a new type of 21st century collaboration based on personal desires of expression (what I buy, what I suggest to others) and textual production through features like the “Customer Reviews,” which dominate the product description page.

The possibilities are made even more personal when we consider the language that many successful Web 2.0 sites employ to make users feel like a part of a supportive community. To ask students in a classroom to refer to each other as “friends” is sure to draw chuckles at best, skepticism at worst. Yet sites like MySpace and Facebook only exist to connect users through electronic friendships.

Though dropping the “friend” moniker, the more professional site LinkedIn refers to a user’s contacts in a network, and myriad commercial sites like Amazon lull users into a sense of security by referring to our “fellow” customers who may be “just like us.” This focus on amicable rhetoric undoubtedly alters our view of community specifically by fostering “a sense of” community. This general feeling of being a part of a supportive, similar, and knowledgeable community complicates my earlier definition and requires we redefine our own communities in the classroom.

To focus on Web 2.0 is to focus on user interaction. But to focus on interaction asks us to look more closely at access. Concerns about the materiality of access where users face myriad options and challenges to computers, Internet access, and proficiency are valid. Beyond this, though, the issue of access also concerns temporal favoring. When the original author or empowered stakeholders are unduly privileged, a late-coming audience takes on a role of retorting and commenting on something that has already taken place, and already taken its place on the shelf of academic thought.

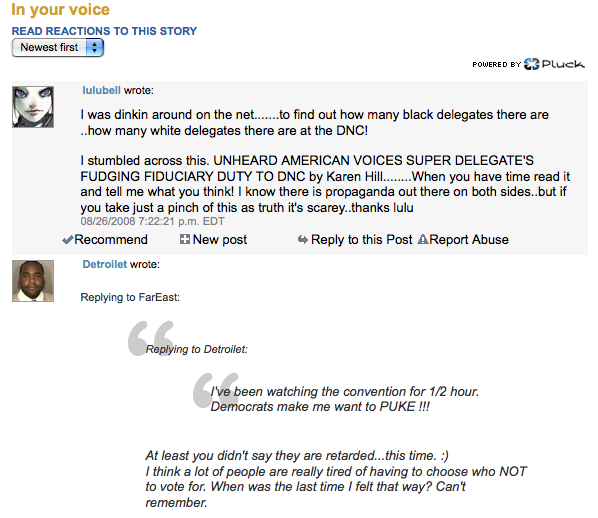

For example, think of a comment section on a popular news story, such as this one from an online article (Zachary Gorchow and Todd Spangler, 2008) on August 26, 2008 in the Detroit Free Press:

As a result, what Web 2.0 technologies offer us, is a glimpse into a future discourse I am referring to as versioning, which takes into consideration that as new voices join a conversation, the direction and outcome of the conversation itself changes. In the same way new software releases are labeled 10.1 and 10.12, etc. our texts—both social and academic—are undergoing subtle changes when delivered in different modes and occasions.

For example, a quick gloss of many Works Cited pages may refer to the same article written by Author X that appeared in Journal Y at some past date. Although the article may be commented upon, anthologized, or modified by succeeding editors, the initial text is still privileged as the original, and hence, “true” text.

Web 2.0 offers us different versions of the same text that can be acted upon, which then may change the course of the conversation and the text itself. So the same Text by Author X is still initially printed in Journal Y, but then it is shown as a lecture on YouTube in a slightly modified way, to which bloggers then comment on and invite comments from, perhaps in a semi-anonymous wiki environment. After the initial text makes the rounds on these different venues, it becomes a completely different text, and the conversation that beget the more recent text gets privileged over the original.

Examples abound for this process; everything from Ede and Lunsford’s versioning of their articles on audience, to editions of books on collaboration by Bruffee, even to deluxe editions of CDs or DVDs. But none of these examples fully take into consideration the instantaneous versioning offered on the web.

Web 2.0 offers us the role of co-collaborators, but also challenges us to determine what is concrete and what is ethereal. In this way, an original text is not only not canonized, it may even be considered obsolete if not a part of this versioning process. We need to realize that students are not only receivers of these varying versions, but they are also potential active co-collaborators for the text.

Thus versioning, as a model of writing, revision, and reception in post-Web 2.0 technology, is inherently collaborative in that co-authoring and recontextualizing is necessary for there to be new versions of a particular text. This new model is not merely re-placement or even minor modification in the mold of revision (such as editing for length, or author-initiated revision for new audiences), but an asynchronous co-authoring that uses an original text as an inspiration for a conversation-fueled authoring of a new text, or texts.

The interactive nature of Web 2.0 technologies facilitates this give and take that neither over-privileges the original author or text, nor wildly changes the content of the ultimate text. To think of revision of texts in light of Web 2.0 as versioning places the focus of composing back squarely on the interaction, collaboration, and process required for nuanced writing.