A New Sense of Community

According to the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), as reported in a featured front-page story in the Detroit Free Press, “technology-literate” students should be able to “create media-rich presentations for other students on the appropriate and ethical use of digital tools and resources” by the time they graduate from high school. The same article recommends that children aged 4-8, in prekindergarten to second grade, should be able to “in a collaborative work group, use a variety of technologies to produce a digital presentation or product in a curriculum area” (Lori Higgins, 2007, p. 8).

According to ISTE, students should be able to use technology to collaborate before they can even compose academic texts.

This is where our expectations of young students meet the inevitability of the culture in which we are educating them. It is not uncommon these days to walk into nearly any composition classroom on nearly any campus and find students typing and clicking on personal laptop computers, some of which may be connected to the Internet via school-provided WiFi connections.

Students are now actively engaging in creating texts via websites like Facebook that rely on users and their content-producing text to exist. As a result, students are literally bringing outside texts, communities, and practices to composition classrooms each time they log on to the Internet. They are already collaborating and composing before lessons are even given.

Witnessing student-users actively participating in such an interactive and textually-dependent medium is the first step to realizing what Web 2.0 technology can teach us about collaborative composition.

Within Web 2.0, users create text in order to populate sites with data; in turn, users can access their (and others') data virtually from any Internet-connected website. As a result, Web 2.0 sites are traditionally viewed as more “useful” than previous generations of websites because of the possibility of transferable interactions—such as the ability to communicate, sell goods, or make a user’s life easier. Among these newer sites, Google Documents, CraigsList, and Twitter are three of the more popular and colorful examples of this pragmatic approach to the web.

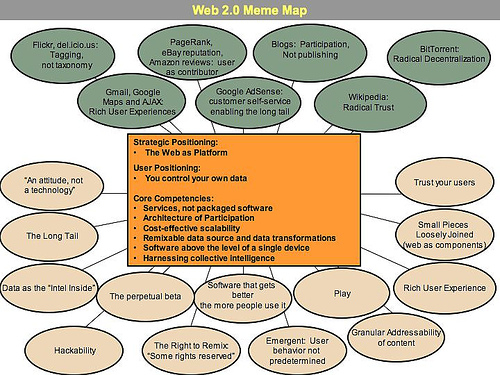

This is what was meant by technology industry vanguard O’Reilly Media in their 2004 conference when they targeted the “web as platform” as the cornerstone of any site deemed Web 2.0. Likewise, their resulting “Meme Map” shown here illustrates some of the commonly perceived secondary traits of this technology.

Of particular note, primary author Tim O’Reilly focuses first on the technology, but then on the user as he or she “control[s] [his or her] own data” (O’Reilly, 2005). The data in this case refers to the text (including written text, photo uploads, hyperlinks, etc.) on each Web 2.0 site; and each of the periphery bubbles are connected to the central ideas of platform and user by incorporating both textual reception and production, a major difference from Web 1.0 sites.

What lies underneath this process is a new wave of attitudes towards textual production and collaboration that may have far-reaching effects beyond a student writing an email to a friend via Facebook while working on a research paper in Word.

Web 2.0 sites are changing the way users receive, produce, and define text. In a study exploring ways students collaborate and compose in visual spaces (including student-authored websites), Margaret Price and Anne Bradford Warner (2005) conclude that students “are less accustomed to think of themselves as authors, rather than consumers” of visual compositions.

When users write on a person’s Facebook Wall, for example, they are consciously creating a public text meant to be viewed by everyone who visits the profile page. The autonomous author of the posting (as text produced on the Wall is called) retains his or her identity—provided by a corresponding photo and name attribution—but the text becomes situated not only on another individual’s profile, but also on the Internet via Facebook. |  |

User- and text-based Web 2.0 sites provide tools to users combining desires of self-expression and community participation. However, current users may not be fully considering the implications of the public nature of their textual productions. While the above user may have wanted to communicate to his or her friend, and for his or her friends to see his or her posting on the Wall, the near-infinite audience of the Internet opens the possibility that this text may present him or her with the unintentional dissemination and recontextualizing of his or her original message as more users interact with and spread it via the social web of such sites.

Such regeneration keeps Facebook in business, but also raises important questions for how composition teachers discuss audience in relation to similar collaborative textual productions in class.

As Price and Warner (2005) note, students composing for the first time in an online and interactive visual space may find it hard to switch between being consumers and authors. Likewise, Peter Holland questioned the role of authorship in a hypertext environment over a decade ago, stating that “it creates two types of authors/editors, refusing to distinguish between the two: those who write sentences and those who restructure materials” (Holland qtd. in Rebecca Moore Howard, 1995, p. 791). These consumer/author and author/editor binaries vividly display the complexity of being an audience member in a medium of blurred public and private space.

Traditional academic texts may invite audience comments in the virgin margins, and emails may elicit responses by opening new text boxes, but sites such as Facebook literally invite audience members to interact with a person’s privately-composed text in a very public way, which complicates notions of authorship in such interactive and potentially collaborative textual productions.

By continually revising and providing platforms for new content, sites tantalize users with the potential of new discoveries and interactions each time they visit. Users may visit a site multiple times a day to engage with text, and each other. This produces these sites’ most unique selling point for compositionists: the promise of writing for an actively engaged audience.

Unlike previous notions of publishing student work to the web to provide them an audience, Web 2.0 provides students an audience who can write back, interestingly conflating author and audience.

Price and Warner’s (2005) study of composing in visual spaces notes this by saying, “authorship and audience tend to work together: if a writer cares about her audience, she is more likely to feel and behave like someone with author-ity.” Thus, student-users of sites like Facebook deliberately compose to fulfill desires of self-expression and communicating to a greater public audience, which may empower them not only to visit the site multiple times a day, but to interact with the text on the site in new ways.

This likewise not only confirms that “writing is not a solely (or even largely) individual act, but a social one [where] new ideas and texts…are developed intertextually from bits and pieces already out there,” (Johndan Johnson-Eilola, 2004, p. 200) but that users want to do this and, gauging by the popularity of such sites, are comfortable with the virtual spaces in ways that perhaps they have not been in traditional academic spaces.

But this is not the only difference between new and old sites in users’ eyes. Simply put, Facebook is “cool” (as is Twitter, Google, Firefox, etc.) Users are not only buying in to the platform and aesthetic that a site like this provides, but in essence the entire zeitgeist of the community. These sites echo Gail Hawisher and Cynthia Selfe’s (1991) view within composition classrooms over two decades ago that “collaborative activities increase along with a greater sense of community in computer-supported classes”

(p. 58).

In other words, computers support communities, and communities support computers—a combination that provides student-users with a sense of belonging, and perhaps a sense of urgency to continually be a contributing member of a collaborative community.